CONCLUSION

WHAT CAN THESE BONES TELL US?

Radiocarbon dating was attempted to determine the age of the bones. Unfortunately, the process failed because the collagen, which is the material used for dating, deteriorated in the underwater environment. As a result, we will probably never know the age of the bones, but based on other radiocarbon-dated sloth remains from Cuba, we believe these animals lived no later than 4000 years ago.

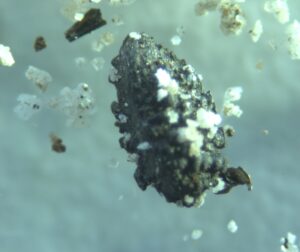

One obvious difference between the Megalocnus and Neocnus bones is their colour. The white, chalky appearance of the Megalocnus bones suggests that they were exposed to the air for a long period of time before they ended up in the water. This indicates a possible change in the environment in this part of the cave, or perhaps human disturbance, but additional tests will be needed to confirm this.

The bones we are studying are technically “subfossils”, rather than “fossils”, because a fossil has been completely mineralized (or fossilized), which has not occurred with these bones. However, some paleontologists believe that the bones of extinct species should also be called fossils, regardless of whether they have been mineralized or not.

STORY IN THE SEDIMENTS

Sediment cores collected in the cave contain seeds from the fruit trees Cecropia and Ficus. The seeds may have been deposited by fruit-eating bats and birds, and indicate that these trees were growing outside the cave thousands of years ago. Interestingly, today, two- and three-toed sloths subsist largely on Cecropia and Ficus leaves. Whether these trees contributed to the diet of Neocnus and Megalocnus is unclear, but it does suggest an intriguing connection between modern sloths and their extinct relatives.

Three-toed sloths such as Bradypus variegatus spend most of their lives in, and eat the leaves of, Cecropia trees.

WHAT IS PALEOCLIMATOLOGY?

Geochemical analyses of stalactites and stalagmites (which grow on the roofs and floors of caves, respectively) can be used to infer changes in ancient precipitation.

Cuba is home to the tallest stalagmite in the world. It is located in Cueva Martín Infierno and measures 66 m tall!

WHAT NEXT?

Our research at Cueva Margarita 1 is a work in progress. We have not yet discovered the answers to many of our questions. Doing so will require significant resources and years of work!

The broad question of ancient extinctions and climate change and our work at Cueva Margarita 1 has ongoing relevance for conservation. By looking into the past we may be able to better predict the possible fate of endangered species in the face of climate change and human impacts on island environments.

Lastly, as an example of international and interdisciplinary collaboration, we hope our efforts will serve as a model for others in their pursuit to understand and protect the natural world.

Conclusion