THE DISCOVERY

DESCENDING INTO THE DEEP

At the cave, battery-powered lights were carried by the divers to illuminate the passage. Stalactites that formed when the cave was dry are present on the roof and walls. Cueva Margarita 1 formed during glacial times when sea level was low and rainwater was able to erode the soft limestone rock. Rising sea levels from the melting of the ice sheets then caused the cave to fill with water.

“Caves have their own personalities. The moment you step into Cueva Margarita 1, you feel that it is alive. But caves are also tricky and dangerous— you have to be careful not to get too comfortable with their beauty.” -Miguel Angel Pereira Sosa

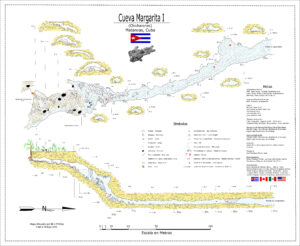

MAP OF CAVE

This map shows top, side, and crosssectional views of the studied section of the cave, which consists of a single chamber that extends downwards and then horizontally for several hundred meters. The present-day water level is indicated near point M-1. The red flags show the locations of the bones.

In the cave, at the edge of the dry gallery and the first submerged gallery (point M-1 on the map), waiting for the divers to return.

The map was made by Bil Phillips using a compass and tape measures. A horse-and-buggy is shown on the side view for scale. According to the Cuban Speleological Society, the official name of the cave is Cueva Chicharrones, but we adopted the unofficial name Cueva Margarita.

THE CAVE AS A LIVING ECOSYSTEM

The cave contains a diverse assemblage of organisms adapted to the cold, dark environment. For example, one fish species evolved to be eyeless, since sight is an unnecessary expense in constant darkness. The organisms co-exist with the cave environment and with each other; birds and bats, for example, use the cave to roost, and supply food and nutrients to other organisms through their droppings. It is important to keep in mind that this is a living ecosystem, and the sloth remains are a part of that.

Scientists must minimize the footprints they leave in any environment they study. Disturbing or modifying a habitat such as an underwater cave could have disastrous consequences for the organisms living there.

DISCOVERY!

The remains of three extinct sloths have been discovered. Two of the sloths, which are located in the deepest part of the cave, are the species Neocnus gliriformis (the smallest of the Cuban sloths), which was arboreal and the size of a medium-sized dog.

We were able to identify the species of sloth by comparing the size and shape of the fossils with other bone remains of these species stored in the National Museum of Natural History of Cuba.

RECONSTRUCTION OF Neocnus gliriformis

There are no complete skeletal reconstructions of Neocnus gliriformis. However, Cuban paleontologist Dr. Carlos Arredondo Antúnez of the University of Havana created this sketch that reflects the form of the animal. Because of the relative completeness of the Neocnus skeletons in Cueva Margarita 1, our work will be important for future studies of this species.

THE GIANT: Megalocnus rodens

Closer to the entrance of the cave are the remains of another species, Megalocnus rodens (the largest of the Cuban sloths). This animal was terrestrial, and was a little larger than a black bear (Ursus americanus).

RECONSTRUCTION OF Megalocnus rodens

There are two complete skeletons of Megalocnus rodens and they provide an idea of how this species would have appeared. The two skeletons were assembled from bones excavated from sites in central Cuba between 1911 and 1918. One of them is exhibited at the National Museum of Natural History of Cuba in Havana and the other is in the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

The discovery